Tea Dust Glaze

Tea Dust Recipes on Glazy

The following glazes and more can be found on my new website, Glazy: https://glazy.org/search?base_type=460&type=550&cone=high

The Complete Guide to High Fire Glazes Tea Dust Recipes

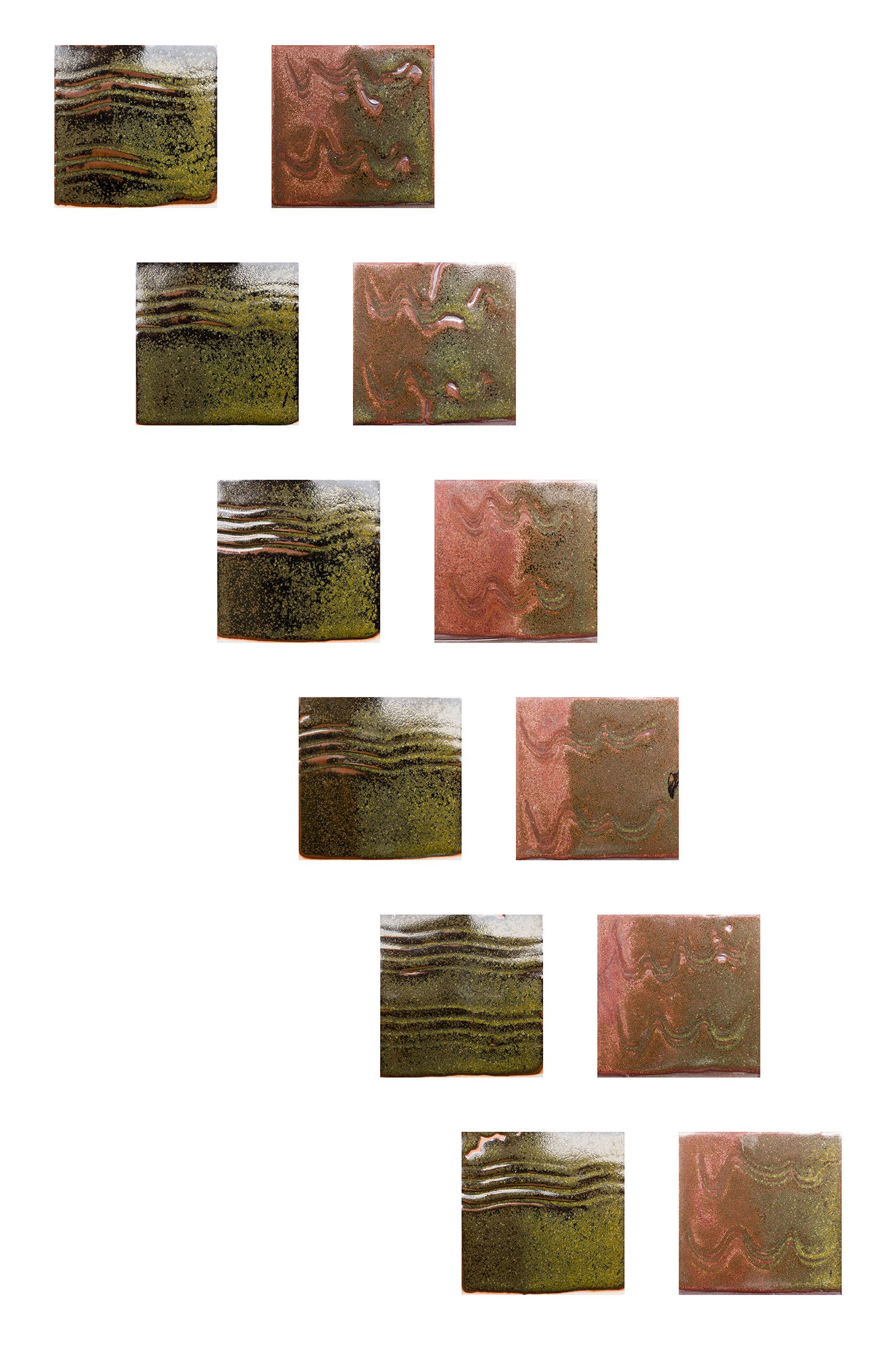

Some tea dust glazes from The Complete Guide to High Fire Glazes. I fired these glazes according to my usual firing schedule, probably too hot and not ideal for the development of crystals necessary for good tea dust glazes. I crash cool to 1000C and then completely shut up the kiln.

Currie 10 Tea Dust

Stoneware, Reduction Cone 10

Porcelain, Reduction Cone 10

Porcelain, Reduction Cone 11

Currie 11 Tea Dust

Stoneware, Reduction Cone 10

Porcelain, Reduction Cone 10

Porcelain, Reduction Cone 11

Coleman Tea Dust

Stoneware, Reduction Cone 10

Porcelain, Reduction Cone 10

Porcelain, Reduction Cone 11

Tea Dust Black

Stoneware, Reduction Cone 10

Porcelain, Reduction Cone 10

Porcelain, Reduction Cone 11

Tessha Tea Dust

Stoneware, Reduction Cone 10

Porcelain, Reduction Cone 10

Porcelain, Reduction Cone 11

Chinese Traditional Tea Dust Glaze

Although the glazes above call all be considered tea dust, in China teadust glaze usually refers to Qing dynasty wares like the ones below. Although tea dust can result in a range of colors and with varying crystal sizes, usually the crystals are very evenly dispersed. (The example below is a Qianlong vase sold through Sotheby’s.)

Qianlong Teadust Vase

Various Teadust Colors

Teadust glaze recipe from 颜色釉 (Colored Glazes), published in 1978 by the Jingdezhen Ceramics Company

Chinese Traditional Tea Dust Glaze Recipes

The recipe above comes from 颜色釉 (Colored Glazes), published in 1978 by the Jingdezhen Ceramics Company. The components of the recipe can be difficult to find today, even in Jingdezhen. Those materials that are still produced probably have different compositions than in 1978. For instance, I’ve noticed differences in Glaze Stone (釉果) and Zijin Stone (紫金石) from year to year. What this recipe has in common with the Western tea dust glazes above is the addition of magnesium oxide in the form of talc, which helps form the tea dust crystals.

The glaze preparation is quite interesting. The ingredients (excluding the white clay (白土)) is ball milled for 30 hours, then white clay is added and the full glaze is milled for another four hours. After adding water, the glaze is sprayed approximately 1mm thick. Firing is to 1250°C in a weak reduction atmosphere.

Tea Dust Triaxial - First Attempt

In part because I’ve had a difficult time finding a reliable chemical analysis for the glaze stone I use, but mostly because I often don’t have much clue what I’m doing, I often use triaxial blends to find interesting glazes. I’m also interested in making glazes for my normal firing schedule, rather than changing my firing for a single type of glaze (like the recipe above that fires to 1240°C).

Because triaxials are limited to three variables, the following tests make some assumptions about tea dust glazes. The top axis of the triaxial will be glaze stone (the “unknown” ingredient), the left axis whiting (the flux), and the right axis silica. I’m certain I need magnesium in the form of talc, dolomite, or magnesium carbonate- I choose 8% talc. I also need some iron, based on past experience and other glaze recipes I choose red iron oxide at 8%.

From the resulting triaxial it seems that crystal growth improves as silica is increased while glaze stone and whiting are decreased.

Traditional teadust glaze. Partial Triaxial, 2% Increments

Tea Dust Triaxial - Second Attempt

For each row of the first triaxial, I like what’s happening in the third column. For the next test, I extend this third column down a few rows to see what happens.

Extended Triaxial. Left- Porcelain, Right- Stoneware

It’s nice to see my educated guesses are working out. Beginning from the fourth row of this second test, it seems like I’m coming close to a glaze that I like.

You’ll notice that the glazes look completely different on the two types of test tiles (porcelain on the left and stoneware on the right).

Just to check that my initial amounts for Iron and Talc are in the right ballpark, I choose the fourth row of this test and make some adjustments. It seems that Red Iron Oxide at 8% additional and Talc at 10% are ideal.

After a few more tests further adjusting the silica, iron, and talc I ended up with the below glaze. While it’s not an ideal tea dust glaze by Qianlong standards, what’s important is that I like it and I can fire it using my usual temperature and schedule.

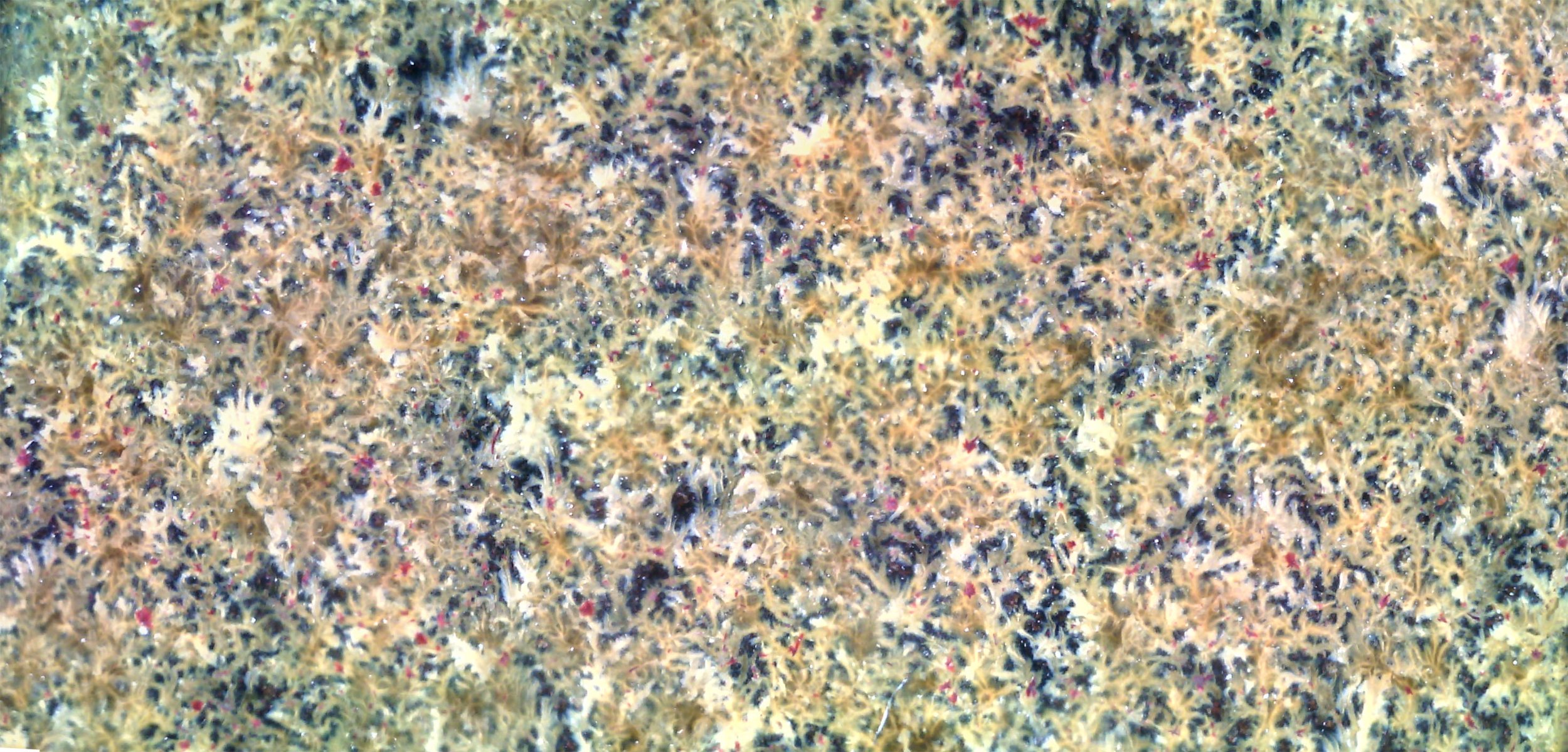

Photomerged microphoto of the same test tile.

The teadust glaze on a small bowl

August 2015 Update

Just to see what would happen if I continued adding silica to the recipe, I extended the bottom-right corner of the original triaxials. As you can see below, incrementally replacing glaze stone with silica leads to an increasingly uniform crystal distribution more closely approximating Chinese teadust glazes. (A feldspar/whiting/silica triaxial for some of the High-Fire Glazes recipes above may have similar results.) Note that in the following tests I increased Red Iron Oxide to 9% (additional).

Second triaxial extension for teadust test glaze

Complete tested triaxial for teadust glaze.

Microphoto of the extended triaxial's bottom-right test

Adjusting Coleman Tea Dust Black

As I did with the traditional tea dust glaze above, I wanted to adjust one of the tea dust recipes in John Britt’s High Fire Glazes to increase coverage of the crystals. The most promising candidate I had found was Coleman’s Tea Dust Black. Starting with that recipe, I designed a triaxial that incrementally increased silica while reducing feldspar (also lowering the alumina).

The original recipe for Coleman Tea Dust Black:

http://glazy.org/recipes/3308

Custer Feldspar 39.81

Silica 25

Whiting 15.74

Kentucky OM #4 12.04

Talc, Magnesium Silicate 7.41

Red iron oxide, RIO 9.3

Total: 109.3

Since I can only change three variables in the triaxial, I choose to modify Custer Feldspar, Silica, and Whiting. I keep the Ball Clay at 12%, raise Talc slightly to 8% (which was a good amount in my traditional tea dust glaze) and set Red Iron Oxide at 9.5%.

Triaxial adjusting Coleman Tea Dust Black. Porcelain, Reduction Cone 10

The most instructive column is the last, with Whiting set at 14%. As silica is increased and feldspar decreased, crystal coverage becomes more even.

Cooling

The above triaxial was slow-cooled. Below is a comparison of the same glaze with a crash-cool to 1000°C.

John Sankey has an excellent article about iron glazes and cooling: http://johnsankey.ca/glazeiron.html

Teadust glaze with slow cooling. After reaching cone 10, immediately close up kiln entirely.

Teadust glaze in fast cool to 1000°C. After reaching 1000°C, completely close up kiln.

I added the recipe for this glaze on Glazy at http://glazy.org/recipes/3557

Potash Feldspar: 28%

Silica: 40%

Whiting: 12%

Ball Clay: 12%

Talc: 8%

Red Iron Oxide: 9.5%

Actually, this glaze is probably too high in silica, and the resulting stony surface not at all like the satiny Chinese teadust glazes. I will try again, increasing the talc and adjusting iron levels rather than simply adding silica. Ideally I would also attempt different firing/cooling schedules, but I won’t change my firings just for a single glaze.

I hope this article shows how to refine a glaze using triaxial testing. With some general knowledge about the type of glaze, educated guesses, experience and a bit of luck, one can design triaxials that reveal interesting new glazes.

Note: I did not cover glaze limits in this article. There are various glaze limits that describe “good glazes”. For instance, on the Glazy page for the triaxial-derived Tea Dust glaze above (http://glazy.org/recipes/3557), you will notice that the glaze sits just outside the Hesselberth & Roy Δ9-10 Glaze Limits. It is up to you to ensure your glazes are functional, especially if they contain oxides that are toxic when leached. However, I find that a lot of interesting glazes are outside of established glaze limits.